Walk into any mall on a Saturday, and you’ll notice it immediately: teenagers tiptoeing around as if their shoes are on loan from a museum, adults hopping over puddles with Olympic-level focus, and someone ordering a flat white while wearing sneakers that cost more than most people’s rent. This is the sneaker economy in 2026, a space where footwear doubles as personality, social signal, and proof of taste. Sneakers are no longer just about comfort or practicality anymore; they’re about the story attached to them and, more importantly, the hefty price tag that comes with it.

Everybody understands that spending serious money on sneakers for a sport you actually play makes complete sense. Runners pay for cushioning and support because knees don’t age gracefully, while basketball players invest in grip and ankle stability to protect their bodies. That logic starts to fall apart once the exact same price tag gets slapped onto sneakers designed primarily for walking between the fridge, the car, and the office.

These days, a $300 sneaker usually arrives with a full history lesson attached. There’s often a detailed breakdown of “premium” materials and carefully named colourways, all working together to justify the cost. What rarely gets mentioned is that the sneaker is often built almost exactly the same as a $100 pair without the exclusive branding. If your daily routine involves little more than commuting and casual errands, mid-range sneakers already handle the job perfectly well, and even knock-offs can manage it without falling apart. But brands like Nike, Jordan, and Adidas aren’t selling practicality; they’re selling the illusion of taste, status, and exclusivity.

Collectors complicate things even further. Some pairs never touch the pavement, with boxes staying sealed and tissue paper remaining untouched. At that point, the sneaker stops being footwear altogether and becomes an object or a piece of art, sitting in the same category as trading cards, Funko Pops, or designer handbags. In that space, ownership itself becomes the point rather than use.

Money habits tend to split people quickly. Some flinch at $50 pants and feel uncomfortable spending $150 on shoes, preferring $10 shirts with decent graphics and glasses that cost next to nothing once you skip showroom markups. For those buyers, value is tied directly to function and lifespan, and labels don’t carry much weight. Interestingly, that same person might happily drop money on video games or entertainment, which only reinforces how relative “waste” really is.

Cheap sneakers often give up after a year, with soles peeling and stitching failing sooner than expected. Brands like Converse and Nike, on the other hand, regularly stretch to four years or more, which is exactly what many buyers are paying for. They’re willing to spend enough to avoid replacing shoes constantly. Once sneakers cross the $300 mark, though, the purchase shifts into something entirely different.

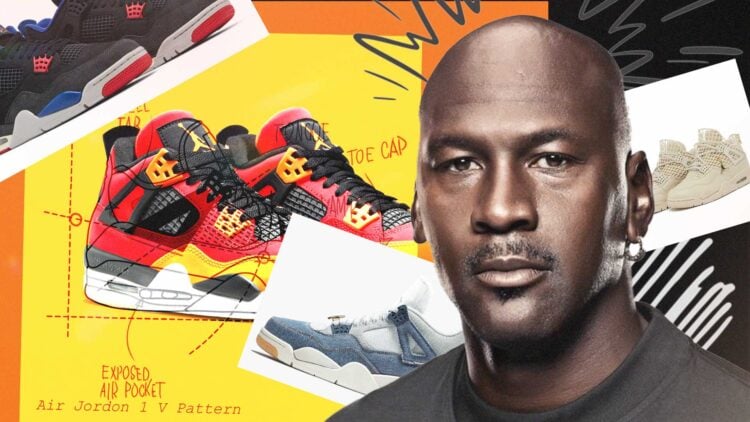

It didn’t always work this way. In the 1980s, sneakers lived almost exclusively on basketball courts and running tracks. Everything changed when Nike signed a Chicago Bulls rookie named Michael Jordan, and by the early 1990s, sneakers had crossed into music, skateboarding, and streetwear culture.

That cultural shift peaked in 2005 with the Nike SB Pigeon Dunk, which Staple designed as a love letter to New York City. Chaos followed the release, with kids sleeping outside for five days in a snowstorm while police eventually stepped in and arrests were made. Today, a used pair sells for anywhere between $30,000 and $50,000, while a mint condition pair once hit $100,000 at Sotheby’s.

The Yeezy 350 “Pirate Black” release in 2016 delivered a similar frenzy, with people camping for days just to secure a pair. Influencer Leanne, known as Monsieur Banana, famously sat outside with a folding chair to lock hers in, and she now owns just under 200 sneakers. Many of them remain unworn, with some carrying four-figure resale values, while stores continue to see kids dropping hundreds backed by early paychecks or parents trying to ease social pressure.

Behind the curtain, production costs stay surprisingly low. An Air Jordan 1 costs roughly $16.25 to make, with materials accounting for $10.75, labour coming in at $2.43, and overhead adding another $2.10. Manufacturing profit barely clears a dollar, yet retail prices soar because demand stays loud and marketing remains effective.

After COVID-19, the hype finally cooled. Lockdowns pushed disposable income toward sneakers, and by 2021 the resale market hit $10 billion, up from $6 billion in 2019. By 2024, prices dipped as buyers became more selective, with pre-owned Jordans surging in popularity. It was the same shoe at a lower price, with less ego attached.

Expensive sneakers only become a waste of money when you expect practicality from something designed for status, storytelling, or collecting. Shift that expectation and the math changes entirely. Money follows meaning, and sneakers just happen to make that reality impossible to ignore.

RELATED: Should You Buy Pre-Owned Air Jordans? Retail vs. Secondhand Sneakers